As Japan enters the ‘Reiwa’ era, India must focus on boosting strategic ties

A map of Japanese business establishments in India also reveals the geographic spread of growth. Maharashtra heads the list with 810 businesses. Tamil Nadu (620), Haryana (609) and Karnataka (529) follow. Adapting US President Calvin Coolidge on America in the Roaring Twenties, it might be that the business of Japan is business. That explains the ups and downs of India-Japanese relations which are now complicated by the urge, inspired by the United States and encouraged by Australia, to contain China through a quadrilateral alliance.

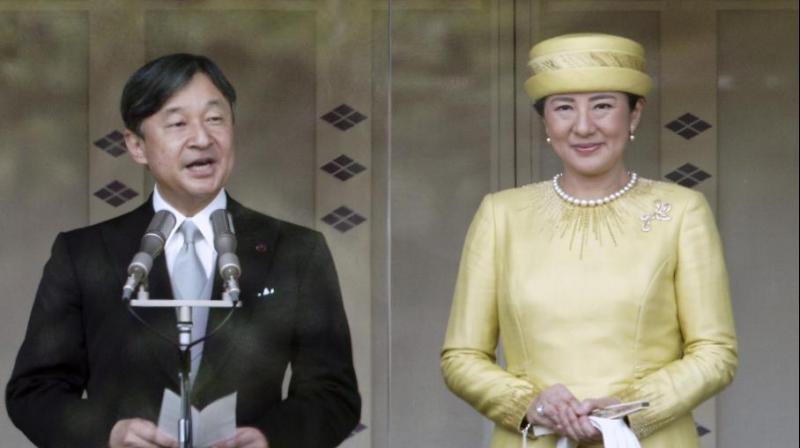

This is a critical time for both countries. Both suffer the ravages of cyclones. Both have to cope with the withdrawal of the waiver of US sanctions for buying Iranian oil. Both face governmental change. India will have a new — or renewed — government after May 23. In Japan a new emperor acceded to the Chrysanthemum Throne on May 1 following the abdication of his father. Now referred to as the Heisei emperor, Emperor Akihito’s 30-year reign was a time of peace and prosperity. Will Emperor Naruhito, the 126th monarch in a 2,000-year line, the world’s oldest, and his Reiwa (“beautiful harmony”) era witness a new form of Asian competition?

Born in 1960, Naruhito is the first emperor to be free of the taint of World War II. His thesis on “Navigation and Traffic on the Upper Thames in the 18th Century” at Merton College, Oxford, makes him Japan’s first modern ruler with an equally modern Harvard-educated, former career diplomat consort in Empress Masako. The emperor is not quite a stranger to India. Aged 27, he paid an official visit in 1987 when he also visited Bhutan.

Japan’s deeply venerated emperors do not exercise even the informal political influence that Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II is said to do. But actions and messages can convey signals without being specific, although those signals may reflect the Japanese government’s thinking rather than individual imperial whim. Emperor Hirohito’s phlegmatic “The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage” broadcast on August 15, 1945 was one instance. The tours of Okinawa with its bitter memories of fighting the Americans and of Pacific battlefields that suffered the most during World War II that his son, Emperor Akihito, visited almost like a pilgrim, was another.

Similarly, Naruhito’s visit to Bhutan only a year after diplomatic relations were established helped to raise the international profile of the small, landlocked and secluded Druk kingdom that was almost entirely dependent on India. A small gesture like wearing a kho, the knee-length Bhutanese robe that looks rather like a Scottish kilt, made the prince extremely popular with the Bhutanese who had only recently asserted themselves diplomatically by moving out of India’s tutelage and starting bilateral talks with China on a disputed, undemarcated 470-km border which exploded in the Doklam crisis of 2017. The engagement Prince Naruhito initiated led to a lively increase in tourism, economic cooperation and high-level exchanges, as well as an implicit strategic partnership between two countries facing problems with China.

New Delhi was the recipient of another of Japan’s coded signals when no Japanese Prime Minister visited India for 23 years. It was a reminder that India’s economy was stagnating with a per capita GNP that was less than one-tenth of South Korea’s. Such backwardness offered little scope for trade and investment, the most important drivers of Tokyo’s diplomacy.

Two successive Japanese Prime Ministers (Nobusuke Kishi and Hayato Ikeda) paid visits in 1957 and 1960, each within three months of taking over. The next prime ministerial visitor was Yasuhiro Nakasone in May 1984. Then, as India began tentatively to respond to altered conditions, Toshiki Kaifu visited in the spring of 1990, almost presciently on the eve of P.V. Narasimha Rao’s epochal reforms. The first two visits in quick succession, the long interval, and then the shorter gap of six years, provided a thermometer of India’s economic health.

The turning point was when Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori’s 114-member delegation, including 14 senior officials, 41 special invitees, mostly business people, and 59 journalists, reached Bengaluru in August 2000. He and Atal Behari Vajpayee established the “Global Partnership between Japan and India”. The even bigger breakthrough was in April 2005 when Prime Ministers Junichiro Koizumi and Manmohan Singh initiated the annual Japan-India summit meetings that have since been held in alternate capitals.

If the economic relationship is still not buoyant, it’s mainly because of India’s poor infrastructure, and the ruling National Democratic Alliance’s unfulfilled promises of 2014. Japan can invest in high-speed railways but that alone will not revive India’s economy if manufacturing is at a standstill, unemployment is rising and incomes are falling. Neither demonetisation nor the GST has succeeded in eliminating black money. Nevertheless, India’s share of Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment rose from $3,218 million to $4,252 million between 2016 and 2018, while Japanese exports to and imports from India during the same period stood at $11,009 million and $5,499 million respectively.

A relatively recent Japanese foreign ministry document cites India’s democracy, vibrant market economy, high growth rate, food self-sufficiency and strategic position astride Japan’s oil lifeline as being of vital interest to the Japanese. Without that reappraisal, a high-flying ambassador like Yasukuni Enoki may not have set the diplomatic dovecotes aflutter with talk of Japan-India-China talks. Nor would Shinzo Abe, the Prime Minister, have started alarm bells ringing in Beijing by including India in his proposed Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with the United States and Australia.

Therein lies the rub. It might flatter India when US President Donald Trump replaces “Asia-Pacific” with “Indo-Pacific”, but the reasons for the revival of Mr Abe’s on-again-off-again Quad proposal and its likely impact deserve careful examination. Japan’s economic interaction with China is so profound that it can afford to take political risks. Whether India has the capability or the finesse to follow suit is another matter.