Dilli Ka Babu: Existential crisis for CIC

Beyond vacancies and growing backlog of cases, which are functional issues, there is a deeper existential issue at the CIC.

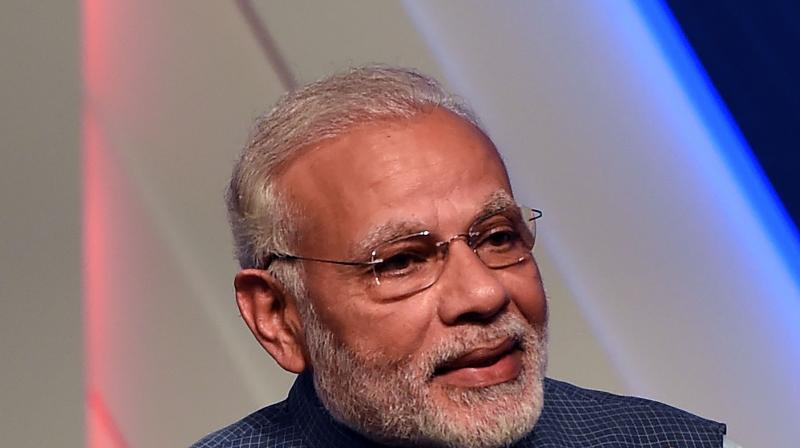

After 12 years of operating from different locations, the Central Information Commission (CIC) has finally got its own building. The building was recently inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

But the CIC has more serious issues to deal with than inadequacy of space. Since 2016, the national watchdog for transparency and accountability has been functioning with depleted strength.

The CIC is working with seven information commissioners, including the Chief Information Commissioner, against a sanctioned strength of 11. Of the seven information commissioners, three are retiring this year.

There are four vacant positions for 18 months now and the government has failed to fill these despite advertising the vacancies two years back, in 2016.

The situation, reportedly, is repeated in the states with several information commissions throughout the country operating without even a chief information commissioner or with a depleted strength of information commissioners.

Many state information commissions such as Maharashtra, Nagaland and Gujarat have been functioning without a CIC.

In West Bengal, Sikkim, Kerala, Odisha and Telangana, vacancies have led to a rise in the number of pending cases.

Beyond vacancies and growing backlog of cases, which are functional issues, there is a deeper existential issue at the CIC.

While the CIC is all about transparency and disclosure of information to the public, apparently, it is exempted from disclosures about its own functioning!

A recent attempt by an RTI activist seeking information on appointing information commissioners for the CIC was denied by the department of personnel and training (DoPT). A wall of silence met the RTI request. It’s all a big secret!

Of course, sometimes it is heartening to note that the CIC will not hesitate in rebuking its own officials for violation of the RTI Act under which the appellate authority functions.

Information commissioner Divya Prakash Sinha recently pulled up joint secretary (law) and other officials when they refused to part with information requested by transparency activist R.K. Jain.

Mr Jain had reportedly sought to know, from the CIC, the action taken on 113 communications received in its legal cell from its dak (mail) section during April-June 2013. But he was not provided with any information.

Mr Sinha said that by refusing to disclose the information sought, the CIC showed a regrettable disdain for provisions of the RTI Act.

But perhaps the biggest challenge for the CIC is the alarming rise in pending cases and also the time taken to deal with them. A recent study has stated that the estimated time required for the disposal of an appeal or complaint has gone up to as high as 43 years in the case of West Bengal, followed by six years and six months in Kerala and five years in Odisha!

Moreover, the CIC has also been accused of giving misleading information about the number of appeals and complaints pending before it.

In response to the query on the number of pending cases as of October 31, 2017, in its initial reply, the CIC stated that 21,097 appeals and 3,533 complaints were pending.

However, in a subsequent reply, the CIC changed these figures to 20,484 appeals and 3,460 complaints.

No explanation was given for providing a different set of pendency figures for the same time period.

If information commissions, at the Centre and in the states, continue to evade real accountability to the people, they cannot bridge the trust deficit with the public.