India's regional policy: Still meddle and muddle

Much as we would like to exalt Jawaharlal Nehru as the founder of modern India’s foreign policy, like all other major countries our policy too derives its basis from one man, France’s Cardinal Richelieu, who enshrined national interest as the only guiding principle to conduct affairs with other nations. The French have an elegant phrase for it. Raison d’état. Richelieu rejected the notion that policy should be based on values and sentimental considerations. He believed, as we all still do, that the State has permanent interests, the singular pursuit of which requires much intellectual and moral flexibility. He believed that the only challenge facing a policymaker is to decide what the national interest was and what it required? It was this singular pursuit that had Catholic France intervening in the Thirty Years War (1618-48) on the Protestant side to block the increasing power of the Pope. At Richelieu’s prompting, the philosopher Jean de Silhon defined the concept of reason of state as “a mean between what conscience permits and affairs require”.

How we see our national interest depends on how we see ourselves. Therein lies the rub. The rump Republic of India sees itself as the successor to the British Raj, which left these shores in 1947. For the two centuries that Britain was the paramount power in India, India’s national interests were synonymous with Britain’s. The paramount power’s paramount interest, as far as India was concerned, was to keep the goose that laid the golden egg healthy and well. Lord Curzon of Kedlestone, who was Viceroy of India (1898-1905) and later Britain’s foreign secretary (1919-24), is still regarded by many of our foreign policy elite as the man who outlined India’s grand strategic vision and its focus on fixing borders. It is argued by them while the political context may have changed, geography has not. However, while physical geography may have not changed, political geography has changed drastically. Afghanistan is no longer the glacis on which the war for India will be fought. Neither are Tibet and Xinjiang buffers against northern threats. The threats are at the doorsteps now.

In the immediate period after 1947, India’s foreign policy was still conducted by the Western-educated elite who had imbibed their lessons in Cambridge and Oxford and believed they were legatees of the white man’s burden, including the defence of India. India’s immediate neighbours, for their own reasons, still see India’s conduct towards them largely in terms of a continuation of the British legacy. It didn’t help very much when the Oxbridge elite were followed by the St. Stephen’s elite, who were also mostly cast in about the same laat sahib mould.

Consequently, our diplomats have tended to be overbearing with our smaller non-hostile neighbours, often treating them like errant schoolboys. This is the constant lament heard in the neighbourhood, whether it is in Colombo or Kathmandu. Increasingly, such voices are heard in Thimphu as well. With Bangladesh too, we have rapidly descended from being the liberator to the neighbourhood bully. The dominant Indian discourse of the “demographic aggression” by Bangladeshi migrants has created a certain unhelpful mentality in both countries. What after all must a nation think when its larger neighbour thinks of it as an unending source of human vermin?

It is interesting that we don’t nurture a similar attitude towards Nepal, whose unabated and facilitated migration in India possibly exceeds that from Bangladesh. But there’s a crucial difference. The Bangladeshi migrant is usually a Muslim while the Nepali migrant is always a Hindu. Unfortunately, many of our leaders still see Muslims as invaders, while not seeing India as a nation of immigrants and forgetting that the vast majority of South Asia’s Muslims are converts who sought escape from the inequities of the Hindu order.

To add to our woes, we still seem to be wearing those Curzonian blinkers that have bequeathed us the Great Game mentality with its focus on highways, railway lines, sea lanes and ports as military threats. South Block still doesn’t seem to have realised that modern military means and technology have made the theories of Mahan and Mackinder largely irrelevant. It is this infantilism that makes us see every Chinese investment in the cash-starved region as a threat to India’s hegemony, when even our worst fears about Hambantota or Gwadar actually make them juicy and easy targets.

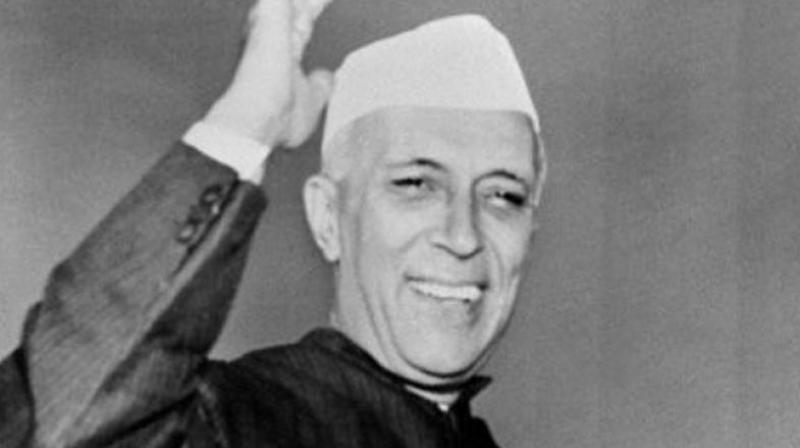

While excoriating foreign secretary Earl Russell in the House of Lords on February 4, 1864, Edward Stanley, Earl of Derby, said: “The foreign policy of the Earl may be summed up in two short homely but expressive words — meddle and muddle.” But we are now no longer prepared to behave like Lord Curzon either. The tension between that Curzonian tendency to meddle and the passive spirit of Nehru to muddle still persists. We see this manifested in New Delhi’s policy responses to the current situations in Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh or the Maldives — with more muddle than meddle. The muddle in South Block is not due to the limited number of options. There is no L’embarrass des richesses, but a poverty of clarity.

The most significant development of this century so far has been the rise of China as an economic powerhouse, with its military not lagging far behind. Speaking to Singapore’s foreign minister Geo Yeo in July 2010, then Chinese foreign minister Yang Jeichi, responding to criticism about China’s assertiveness, just said: “China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.” Indeed it is, and at this point in time even India is much too small to be able to compete with it in its spree of chequebook diplomacy. Most of India’s regional neighbours are poor countries, and if their adversity forces them not to look at Chinese gift horses in the teeth, then we must understand it. In other circumstances, we too might have acted similarly.

But our inherited Curzonian vision and now a little bit of American induced notion of containment are pushing India into a confrontationist posture with China. India will do well to remind itself that of the Quadrilateral that is being increasingly talked about, only India has a long and contentious land border with China. The other three Quad players are hooked up to China’s growth engine and are also most responsible for its rise — America with its trade profligacy, and Japan with its massive investments and transfer of technology. India must be wary about becoming their cat’s paw.

Delivering the valedictory address to a recently-held conference of South Asian scholars at the Unesco Madanjeet Singh Institute of South Asian Regional Cooperation and Coordination at Pondicherry University, my advice to fellow South Asians was that they would do well to take in all the Chinese financial assistance coming their way, and not be too worried about it. I recalled the dictum enunciated by Walter Wriston, the legendary Citibank chairman, who told my class at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy: “Countries don’t go under, they just roll over”. Indian corporations are experts at rolling over debts, and that if the neighbours should need advice on how to do it they could just knock on our doors. Hence they should remember this song from the 1970 Manoj Kumar film Purab aur Paschim:

Koee jab tumhaaraa hriday tod de,/ Tadapataa huaa jab koee chhod de,/ Tab tum mere paas aanaa priye,/ Meraa dar khulaa hai,/ khulaa hee rahegaa, tumhaare liye.