Tourism is changing Ladakh: It’s a boon, but it also creates new crises

Scholars do not agree on the etymology of the word Ladakh. For some, it is the “Land of the Passes” (la); for others, it is the “Land of the Lamas”. Whatever the correct interpretation, it is, for both reasons, certainly one of the most stunning places on earth.

Visiting Leh earlier this month, I had the opportunity to experience once again the celebrated peace of the place and the hospitality of the Ladakhis.

The region has, however, completely changed since my first visit in 2002. Along with the majestic gompas (monasteries), you can now see a myriad of cement shops symbolising daily faster development; all due to the craze of the Indian and foreign tourists for the mountainous region.

Though the Kashmir Valley constantly draws the attention of the world media and the chancelleries in New Delhi, it is geographically a very small portion of the state and Ladakh is far more strategic for the nation, with two unfriendly neighbours on its borders.

At the time of Kashmir’s accession to India in October 1947, political and economic power was offered to Sheikh Abdullah’s National Conference government in Srinagar despite the fact that Ladakh covered 70 per cent of the area of J&K under India’s administration. Dominated for the past 70 years by successive Srinagar governments, Leh has for decades been deprived of any say on its own development. It is finally slowly changing.

Soon after Independence, when the Pakistani hordes’ motto was: “Let us liberate our Muslim brothers from the yoke of the Hindus”, Ladakh seemed at first safe. It was without taking into account the infinite greed of the new Pakistani leaders. According to their “two nation” theory, Muslim-dominated areas of the subcontinent were to become part of Pakistan and the Hindus, Sikhs and others were to remain with India. But the theory was thrown to the wind when Karachi decided to also liberate their Buddhist “brothers” in Ladakh, not for ideological reasons, but for the treasures of the Buddhist gompas that became a lure for a finance-starved Pakistan.

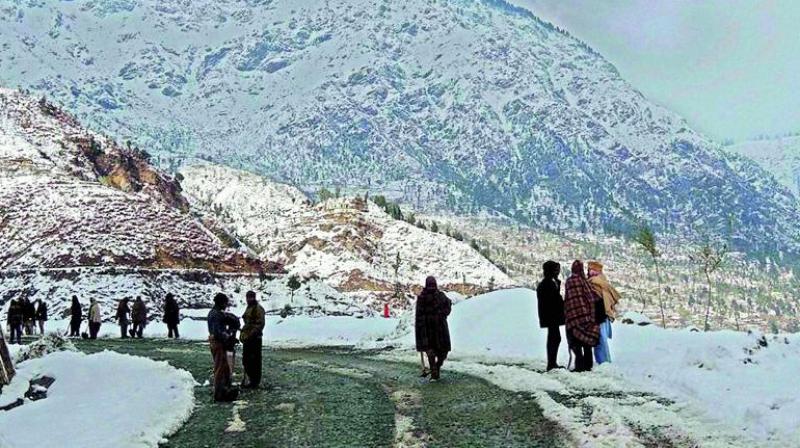

It is then that two young Buddhist officers from Lahaul, Captains Kushal Chand and his cousin Prithvi Chand, offered their services to the nation to stop the raiders — the duo managed the incredible feat of crossing on foot in winter the snow-bound Zoji-la between Kashmir and Ladakh — they were accompanied by a small caravan of men and mules carrying arms and ammunitions. Though Buddhists are believers in ahimsa, they risked their lives to save Ladakh. Without the knowledge of the Army Headquarters — which would have been reluctant to permit such a risky operation — the young captains crossed the pass and reached Leh safely — to prepare a surprise for the raiders.

They fought against the weather, the altitude and the hordes of invaders to defend their co-religionists — both were awarded the Maha Vir Chakra (MVC), the second-highest decoration in wartime.

The Lahaulis’ was the first of a long saga of daring acts by young officers who, since then, have bravely defended Indian territory.

It is worth visiting the Hall of Fame near the Leh Airport where their exploits, as well as those of other local heroes, are depicted.

One should mention Col. Chewang Rinchen, who was twice awarded the MVC — first for having stopped the advance of raiders in the Nubra Valley in June 1948 and the second, for the bravery he displayed in the Turtuk sector in December 1971.

More recently, Maj. (later Col.) Sonam Wangchuk (another Buddhist soldier to be awarded the MVC) and his Ladakh Scouts recaptured some of the crucial peaks occupied by Pakistan during the Kargil War in 1999. One still has the image of Wangchuk, praying to the Dalai Lama, the incarnated Bodhisattva of Compassion, to give him the strength to save India, his nation.

Immediately after J&K’s accession to India, Ladakhis took the stand that their future was linked with India, though culturally, racially and linguistically they were closer to Tibet.

In May 1949, the first delegation of the Young Men’s Buddhist Association of Ladakh led by Kalon Chhewang Rigzin met Jawaharlal Nehru in Delhi and presented him a memorandum: “We seek the bosom of that gracious Mother India to receive more nutriment for growth to our full stature in every way. She has given us what we prize above all things — our religion and culture.”

Kushok Bakula Rinpoche, the head lama of Ladakh and a long-time minister in Srinagar, was another one who, as early as in the 1950s, defended the rights of the Ladakhis. Bakula never chose the path of confrontation — he always tried to get greater autonomy by working with the system. As his methods did not fully succeed, faced with New Delhi’s decades-long apathy and the “larger issue of Kashmir”, in 1989, the Ladakhis had no alternative but to resort to an agitation, a concept alien to Buddhism. Greater autonomy and closer links with India were not granted till the Ladakh Buddhist Association organised a non-violent movement — after many frustrating decades, Ladakh was finally offered an Autonomous Hill Development Council as a compromise in 1995. Though the chairman and his executives, councillors (ministers) have vast executive powers on paper, they often face a frustrating situation with Srinagar.

But Ladakh is changing. Today, tourism is a boon… and a bane.

Last year, more than three lakh tourists literally descended on Leh, providing employment, but also creating the first water crisis of the region. While the population is far better off economically, the environment is clearly in peril. How to sort out the dilemma?

Sonam Wangchuk, a Magsaysay awardee and the inspiration for one of the characters of an Aamir Khan movie, The Three Idiots, believes that the solution is to change the pattern of tourism in space and time; he advocates bringing tourism to the villages (space) and the whole year long (time).

It may work for a time, though there is no easy solution, whether it is in Ladakh, Uttarakhand or Himachal Pradesh, mass tourism has too many negative aspects.

Ladakh has an advantage over other regions — it has a more responsive administration — the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, and with the division status recently granted by the Central government, the region should get better capacity to solve such problems.

On the strategic side, though the Fire and Fury Corps of the Indian Army is watching, the enemy is still at the border.

The opening of a new landport for trade with China at Demchok or Dumchele could be an important confidence-building measure with China — hopefully, it will be discussed during President Xi Jinping’s visit to India in October.

If the political leadership decides so, Demchok or Dumchele could also become a Border Personnel Meeting (BPM) point, where the Indian and Chinese armies meet. It would be the third one in Ladakh.

The opening of a new landport with China would boost the village economy, and satisfy the local population. One day, one can dream of a new route (without crossing a single pass) to Mount Kailash. It would then become the fastest and easiest access to the holy mountain.

In the meantime, Ladakh needs to control its too-fast development.