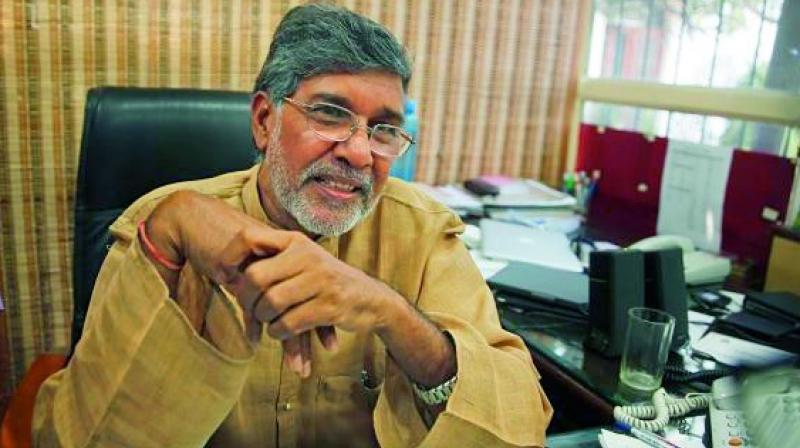

Sunday Interview: Amendment to child labour bill is regressive'

The nation has to decide, we will have to work with the government for a good law and higher budgetary allocation for children.

Kailash Satyarthi, Nobel laureate and child rights campaigner for over three decades, criticises the newly amended child labour bill that permits children to be confined to work instead of being in school. In an interview with Teena Thacker, he voices concern about the amendments and how it failed the children of India yet again.

What do you think about the current scenario of child labour in India?

It’s ironical that India, a land of great tradition and values and the fastest-growing economy in the world, still faces the stigma of child labour in all its worst forms, like child slavery, trafficking, children working in hazardous occupations, drug peddling, etc. It’s a combination of social evil, development disparities and crime.

What are your views about the amendments in the child labour bill? Do you think they endanger childhood?

The old law was obsolete and it endangered childhood; there were inbuilt weaknesses in the law. The fight for a stronger law is still on. This new amendment is regressive. There are major flaws. The definition of family enterprise has blurred a very natural course of engaging children to help parents. There is as yet no definition of an extended family in any Indian law. Also, the number of hazardous occupations earlier 83, has now been brought down to three.

The government argues that the earlier list included children up to the age of 14 and this will apply to age group 15-18 years, but, the question is, when you see the practicalities and operational part of the law connecting these two, then a young girl can go to work as a domestic help along with her mother and the employer can easily say that s/he is not responsible because the amended law makes it easier for the young to work. Similarly, children will be allowed to work in slaughterhouses, leather houses, at beedi making and in glass furnaces in the garb of family enterprises. Our organisation — Bachpan Bachao Andolan — freed 5,500 children in the last five years; 21 per cent of these children were found working in family enterprises. They were trafficked from Bihar and were victims of child labour. Now, these children can never be freed.

Were you satisfied with the debate in Parliament?

I was really shocked. The poverty arguments have been misused by parliamentarians. Some said that since India is a poor country and the families are incapable, the children should lend a helping hand. My argument is — what do they want to showcase: that India didn’t make any progress? The same arguments were used 17 years ago. GDP has grown immensely, how can they bring this issue now? India has made a lot of progress. I was upset to see the discussions, even the Opposition is responsible. It’s the entire political cast who are answerable; they don’t prioritise children. We are the motherland of Buddha and Gandhi and we view our children through the prism of economics. When we talk of children who are non-voters, then the responsibility is much bigger. I definitely admire and applaud the interventions made by some parliamentarians.

You have been acknowledged internationally for your work. Were you consulted on this?

Many times. The minister of labour and I had a series of discussions. It was also promised that they would accommodate my suggestions. Unfortunately, nothing happened. I had thought that my years of fighting for the bringing of a strong law would now come to fruition and the work would continue hand-in-hand with the government, but it now looks that I will have to continue on my own.

What’s your next step?

I strongly oppose it (the bill) and we are examining it to see what can be done. I will try once again and may approach the Prime Minister. There is slight room to amend the list of hazardous occupations and retain all 83 occupations that were in the previous list.

Do you think you will be able to win this fight to end child labour in India?

Definitely. I see the end of child labour and slavery in my lifetime. It’s not merely the law that has to be there. There are so many other things. The poor that live in the remotest areas have started valuing education. They think education is a pre-requisite, education is now perceived as a way to empowerment. There is a paradigm shift across India. I also think schemes like MGNREGA will eventually benefit the poor.

The corporate sector cannot flourish at the cost of exploitation of children. In the last 15 years, the number of working children below the age of 16 has gone down across the globe. It has become much more promising than the last 15 years; the next 15 years are, therefore, critical.

India has supported the United Nations sustainable development goals which look at total eradication of child labour by 2030. Do you think India is focused or is it too ambitious?

I am a hopeful man. I know that the laws are the not the end of the road. We have to find different ways. The nation has to decide, we will have to work with the government for a good law and higher budgetary allocation for children. I am not going to give up. It’s challenging for me, but freedom for children and childhood will prevail.

What’s your formula to end child labour?

I don’t have a formula. We have to build a strong social movement against child labour as well as pump quality education. Education is a preventive measure. Social mobilisation and mass movements are other requirements to end this evil.

Did you ever face political pressure in your quest to fight for child rights?

Several times, directly and indirectly. I have been threatened by politicians, ministers, and even a Prime Minister. But there have been so many social initiatives taken by this government, I have not lost hope.

How focused India is on providing equitable and quality education to children?

India is one of the leading countries that have strongly supported SDGs in the UN General Assembly to ensure quality and equitable education. I am afraid I have to say how can we have “sabka vikas and sabka saath” if we do not include children? We have this kind of law which is giving licenSe to children to work in the name of family values and we talk about providing education.

I am sorry but this regressive law is not helpful and a contradiction. In India, and in many other countries, children are not a political priority. Empathy, love and mention of children are used by all leaders across parties just to put a human component in their voice. However, in budgetary allocations, children are hardly included. This is a global phenomenon.