Can AAP pull off another Delhi victory in 2020?

Though elections in Delhi are due only early next year, various decisions which the Aam Adami Party (AAP) government has taken or proposed clearly indicate that the government is in election mode. The newspapers are full of full-page advertisements about the happiness curriculum which the AAP introduced in Delhi government schools, it proposed to provide free rides to women in the Delhi Metro and in Delhi Transport Corporation buses and has now announced a policy for expediting the process of regularisation of the unauthorised colonies of Delhi. All this would certainly make sections of Delhi’s voters happy, but can that be enough for the AAP, with a declining support base, to win another election in Delhi? In spite of the AAP getting badly defeated in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, there still remains a possibility for the voters of Delhi willing to prefer the AAP over others for another term. Given the mood of voters reflected by the verdict in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, it seems a Herculean task, but not impossible.

The task seems to be extremely difficult for the AAP, given its declining support base. When it contested the Delhi Assembly elections for the first time in 2013, the AAP polled 29.4 per cent votes, giving a tough fight to both the BJP, which polled 33 per cent votes, and the Congress, which polled 24.5 per cent votes. Its voteshare increased significantly to 54.3 per cent during the 2015 Assembly elections, when it won 67 of 70 Assembly seats. This was largely at the expense of the Congress, as its voteshare went down to 9.5 per cent, while the BJP polled 32.6 per cent of the votes, and managed to retain its core support. In between these two elections, the AAP polled 32.9 per cent of votes and the BJP polled 46.4 per cent of votes when the election for the Lok Sabha was held in 2014. There seems to be a systematic decline in the AAP’s support base as it performed badly in the local body elections held in 2017, and polled 26.25 per cent of votes compared to 36.2 per cent of votes of the BJP. Its performance remained dismal during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections as it drew a blank and polled 18 per cent of the votes, lesser than 22.5 per cent votes polled by the Congress. The BJP polled a record 56.5 per cent of the votes in these elections. Looking at the electoral performance of the AAP during the last few elections, one wonders if the AAP could swing the scales in its favour in the Assembly elections due in Delhi early next year.

The task may be difficult, but not impossible — the AAP could still hope that given the improvement which the Delhi government had brought about in healthcare and education, people might consider giving the party one more chance for governing Delhi for another five years, even when they had rejected it completely during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. After all, voters are used to expressing different political choices even when elections are held simultaneously (most recently in Odisha in 2019) or when held in quick succession like in Delhi 2013-2014 and 2015. There are reasons for the AAP to hope that the verdict of 2015 held soon after 2014 could be repeated (if not in a similar scale) in the 2020 Assembly elections, which will be held soon after the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. The repeat of the 2015 verdict can only be a dream for the AAP, but a victory or close contest may still be possible as the AAP remains popular amongst the lowest and lower social segments of voters, both in terms of caste and class, though its popularity may have declined drastically amongst the middle and the upper classes. Its two flagship schemes of primary health and schooling benefited largely the people belonging to the lower and the poor classes.

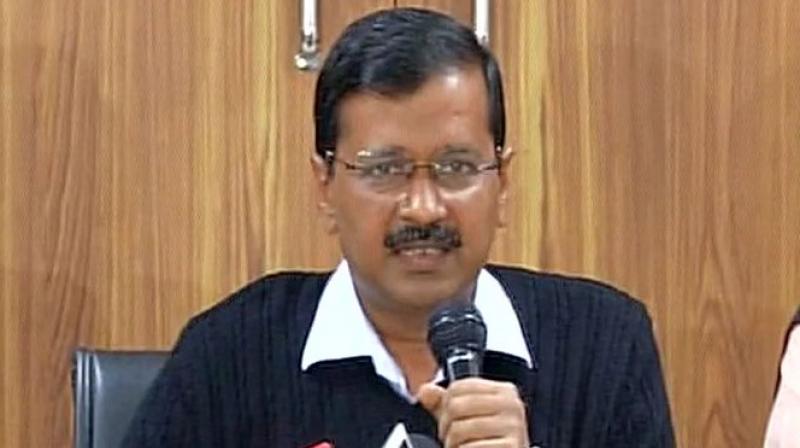

The recent announcement of giving a free DTC bus ticket and regularisation should be seen as an effort to consolidate its support base amongst these sections. There a huge overlap between class, caste and those living in slums, jhuggis and unauthorised colonies — a large number of people living in such localities also belong to the lower segment of society. The recent effort to fasten the process of regularisation of these unauthorised colonies in coordination with the Central government could only help — if not increase — in holding on to the party support base amongst the lower and the poor classes of voters, mainly migrants from eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The AAP government, by making DTC bus rides free for women in Delhi, is trying to be one step ahead of other state governments in their populist schemes like Nitish Kumar’s cycle scheme for school-going girls in Bihar, K. Chandrashekhar Rao’s scheme of Shaadi Mubarak in Telangana, Akhilesh Yadav’s Hamari Beti, Uska Kal scheme in UP, Biju Patnaik’s Biju Shishu Suraksha Yojana and Biju Kanya Ratna, the Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao Yojana in Haryana, the Ladali Yojana in MP, etc. The successes of some governments, and at the same time, the failures of others, indicate that these schemes are not enough for winning elections — there is a need for scheme-plus for electoral success. The Arvind Kejriwal government may be able to hold on or tilt the support of women voters by such schemes, but that may not be enough for the party to win another election. The victory in 2015 was also credited to the personal popularity of Arvind Kejriwal, and even the slogan was “Paanch Saal Kejriwal”, the party would have this handicap in 2020 as Mr Kejriwal no more remains as popular as he was in 2015 — no more creating euphoria amongst the masses.