Partition Memories Come Alive at India Photo Festival 2024

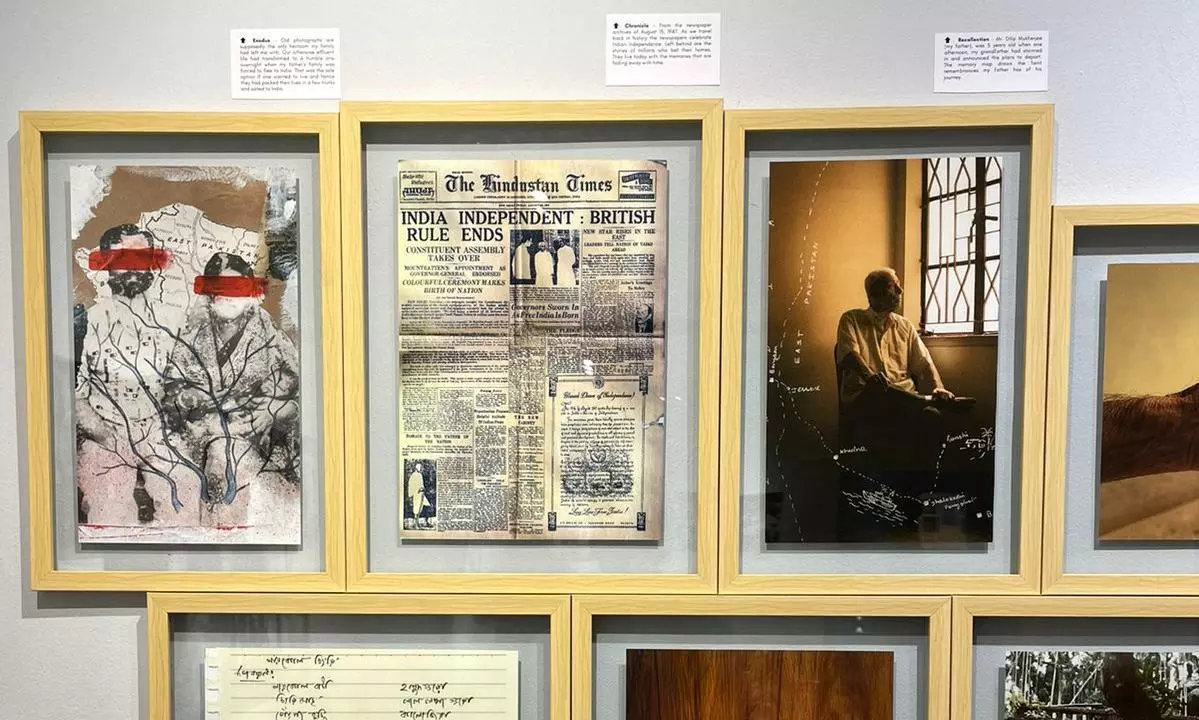

Hyderabad: "It smells like home," said Shubhadeep Mukherjee, with the weight of memory, standing amidst his exhibited work at the State Art Gallery in Madhapur for the India Photo Festival 2024, surrounded by photographs layered with ink, archival letters, recipes, and maps.

Standing in Gallery 3, I found myself unsettled by the strange familiarity of it all. Shubhadeep had used the concept of the invisible home as a portal to a shared past — a collective memory of East Pakistan before the partition that I hadn’t realised I carried.

“I wanted to create something you can’t touch but can feel,” Mukherjee said, standing by a portrait of his father overlaid with a map of Barisal, the village his family left behind during the Partition. “Every house has its own smell. It could be the food, the soil, or even the clothes. And when you leave it behind, you carry it with you, but it’s never quite the same.”

Home, according to Mukherjee, is an idea shaped as much by nostalgia as by loss. His ongoing project, Smells Like Home, is rooted in his father’s Partition story, but it spirals out into larger narratives about memory, displacement, and belonging.

I found myself returning to the title, ‘Smells Like Home’. It resonated because it spoke about the stories I grew up with. Stories of the jamun tree under which my grandmother used to play in Baishari, Bangladesh; of my great-aunt, a dementia patient in Kolkata, still searching for the home she left behind in Bangladesh; of the old house abandoned, the keepsakes, letters, and notes from the war, and so much more.

I shared with him how it reminded me of my own family, most of whom came from Bangladesh, and how his photo essay transported me back to the stories I was raised on. Further, although Hyderabad has been my home for a few years now, the smell of another home where I spent 25 years of my life still lingers in the background.

Mukherjee nodded, as though he understood. “It’s not just the place you miss, it’s the feeling. And memories work the same way. They’re close enough to feel, but just out of reach.”

He began this work in 2021, documenting his father’s memories of leaving East Pakistan in the 1950s. He recorded voice notes and took photographs, but he soon realised that photographs alone weren’t enough.

“A photograph captures the surface, but it doesn’t show you what they felt while speaking about home,” he said. So, he began drawing on the portraits, lines that traced routes taken across borders, shapes that hinted at forgotten toys or childhood dreams, stories in fragmented layers.

“Memories are unreliable,” Mukherjee admitted. “But they’re all we have. They pop up like fragments. One moment a clear image, the next a blur. That’s what makes them so intriguing.”

Interestingly, Mukherjee refuses to use the word “refugee,” a term he finds limiting and derogatory. “These are Partition survivors,” he said, adding “Why should their identities be reduced to a label? It’s a national trauma, not an individual failing.”

His work isn’t just about preserving the past; it’s about challenging how history is told. “History is always collective — this many people crossed, this many died. But it should be personal. Every one of those people had a unique story. That’s what I want to tell,” he said.

He pointed to a piece featuring a handwritten recipe for coconut prawns, a dish his father often spoke about. “Food carries memory,” he said. “This recipe is from Barisal. My father always said they used coconut in everything because their village was full of coconut trees. These little things tie us to home in ways we don’t even realise.”

“Do you think home changes over time?”

“It does,” Mukherjee said. “But for many of the people I’ve spoken to, their idea of home is frozen in time. My father is 80 now, but he still thinks of Barisal as it was when he left, when he was a child. It’s the same for so many Partition survivors. Home isn’t where they are now, it’s where they were before everything changed.”

Standing in that gallery that day, surrounded by his work, I felt it. The weight of longing, the concept of home and the beauty of memory. Mukherjee’s art smelt like home. And for a moment, it felt like home too.