Variety is recipe for success in football

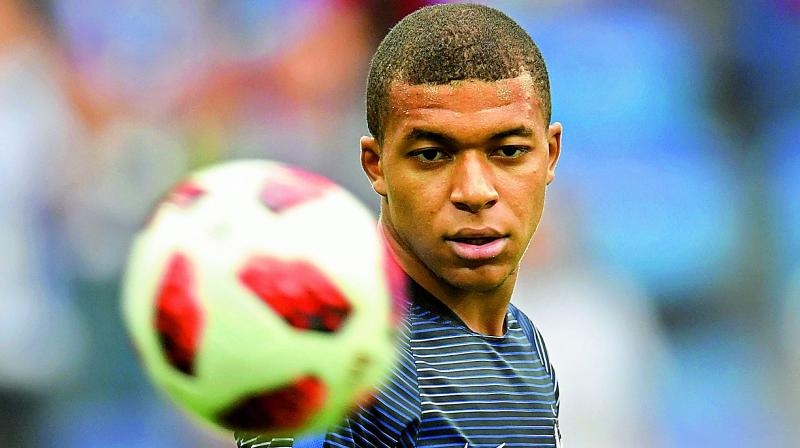

Moscow: If Kylian Mbappe scores a goal against Belgium in the World Cup semifinal on Tuesday, three countries would be celebrating because the Frenchman was born to a Cameroonian father and an Algerian mother. Congo will have a reason to rejoice if Romelu Lukaku does find the back of the net for Belgium, as his parents had emigrated to Europe from the African country.

When anti-immigrant sentiments are sweeping wealthier nations of Europe, the first semifinal of the 2018 World Cup will showcase a multicultural cast that is sure to please idealists. With three fourth of the French squad in Russia being first-generation immigrants and players of African ancestries dominating Belgium’s roster, the match at St Petersburg has raised intriguing questions about race, integration and inclusiveness in football.

Integration of races has always been crucial for success in the beautiful game. It’s not surprising that Uruguay, the most successful international team at the time of the first World Cup in 1930, were the first South American country to embrace black footballers.

Brazil’s resplendent record in the World Cup can also be traced to the integration of all races in the country’s football team. Pele would never have got a chance to play for Brazil had racial prejudice prevailed in his country in the 50s as it had in South Africa during the same period. Brazil’s subsequent World Cup squads have been full of players from white, black and mixed racial backgrounds. Variety is strength in sport as they bring disparate advantages — physical, psychological, technical and cultural — to the table.

Long-time observers of South American football aver that the plight of Argentina stems from their failure to have footballers from different ancestries in their team. Argentina invariably have an all-white squad and it is not a recipe for success if you look at countries that are doing well at the 2018 World Cup. All the semifinalists here, barring Croatia, are full of players from different races and ethnicities.

It is no coincidence that four-time champions Italy, where anti-immigrant right-wing politics always has traction, failed to qualify for the World Cup in Russia. It is never easy for a black player to pull on an Azzurri jersey, as Mario Balotelli would attest, because racism is entrenched even in the highest echelons of football administration in Italy. It would be useful to remember that Argentine football was dominated by Italian immigrants in the early part of the 20th century.

The profusion of immigrants in French and Belgium squads is neither surprising nor praiseworthy because the two countries had plundered Africa through colonisation. France continues to wield control over certain sub-Saharan African countries even today.

If Belgium gave shelter to Lukaku’s parents from Congo, it wasn’t doing them a great service as it had exploited the vast country for many years. The Netherlands, too, benefited immensely in football by giving opportunities to black immigrants from their former colonies. Without Eusebio, an immigrant from their former colony of Angola, Portugal football would have achieved nothing in the 60s.

France won the World Cup in 1998 mainly because of their multicultural cast. Even the success of Germany in recent times and their rising popularity in neutral countries is a result of their acceptance of players from different backgrounds, especially Turkish. A black player in the German squad would have been unthinkable in the 80s. Right-wing politicians will continue to oppose immigration because it is their ideological bread and butter but teams that integrate well have a brighter chance of doing well in football.