Green warriors

The call of the wild grew faint. Rivers dried up, forests thinned. Birdsong and gurgling streams fell silent. Darkening evenings no longer brought out the fireflies and crickets. The greens slowly faded, and the concrete swiftly spread.

Urbanisation has come at a stiff price. Over time, concrete jungles swallowed up lush green forests and perennial rivers dried up into parched lands. But a few eco warriors decided to take the long, tough, lone walk — to make the earth green again and gift the planet its lost charm. The resolute and tenacious pioneers slowly gathered followers along the way, and they are now leading the march towards a greener world.

From Rajasthani villager Shyam Sundar Paliwal who started the custom of planting 111 trees when a girl child is born, to Jadav Molai Payeng from Assam who built a 1,360 acre forest on the banks of the Brahmaputra, these green warriors are spearheading a change — for a better, greener tomorrow.

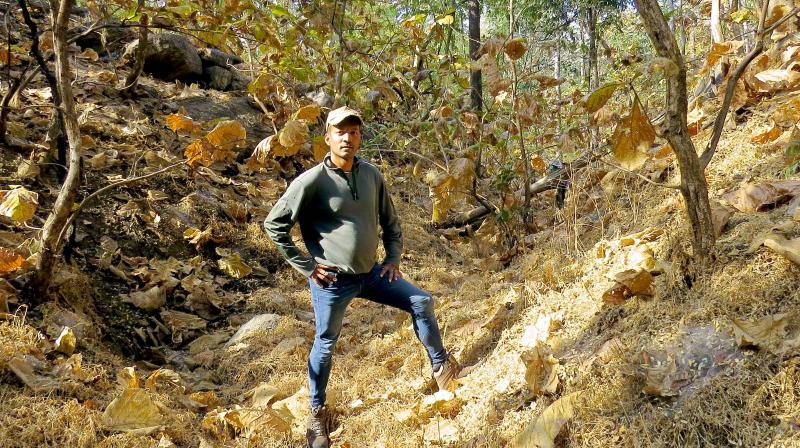

Abhishek Ray

Song of the woods

Even as pockets of forest lands are being reclaimed for developmental activities in various parts of the country, this music composer and wildlife enthusiast has turned a barren hill near Corbett National Park in Uttarakhand into a thriving wildlife reserve. Abhishek Ray, a music composer who has rendered music for award-winning films like Paan Singh Tomar, Welcome Back, Saheb, Biwi Aur Gangster, has dedicated all his savings to build Sitabani wildlife reserve. This verdant expanse is home to around 350 species of birds and several animals now.

The idea of a wildlife reserve came to him when he stumbled upon an excessively degraded hill while carrying out a big cats’ census in the Corbett National Park. “I have been assisting the forest department in conducting a census of big cats from the age of 14. During one such time in Corbett, about 15 years ago, I came across a hill that was completely barren, devoid of any kind of vegetation due to continuous slash and burn agricultural practices being performed there for years. The sight of this degraded area, surrounded by a thick sal forest, pushed me to buy the land,” says Abhishek.

The hill area, which was used for farming earlier, had been experiencing human-animal conflict. On one side of the hill there is a small tributary of the Kosi River, where animals used to go to drink water and while passing the hilly area, animals, including deer and big cats, would destroy crops and cattle. “I realised that it is part of the wildlife corridor and needs to be returned to the forest. I spent whatever savings I had and gradually acquired pockets of the land one after the other for years from different families,” recalls Abhishek.

The music composer, who is also a certified big cats tracker and wildlife conservationist, then started planting trees and dug up a water body in the land. Abhishek adds, “Soon, the water body lured several animals to its banks, as they would come to quench their thirst. We came up with a rainwater harvesting system so that the area never runs out of water. We also focused on planting endemic trees like banyan, jamun and wild mangoes, so that it benefits wildlife rather than humans, thus you won’t find any foreign plantations there.”

One can see several colourful birds flying across Sitabani. It also houses animals like the Indian leopard, tigers, elephants, wild bear, jackals, striped hyenas, otters, and more.

The wildlife reserve has strict rules, like no lights at night since it disturbs the leopards and tigers in the area. The other rules are no loud music, ‘first right of the way’ to animals which means one has to move aside and allow the animal to pass if one encounters a wandering animal.

Abhishek Ray has recently composed Earth Voices to sensitise people towards the destruction of wildlife habitats across the country. “We have lost 50 per cent of wildlife on the Earth in the last 30 years. This symphony is a message to the people to ensure the protection of wildlife. The term ‘wildlife’ is the greatest conspiracy hatched by the human civilisation to control and kill all free animals that live on Mother Earth. People feel they have the privilege to enjoy the resources of the planet, including forest lands and water bodies, meanwhile confining the animals to cages and zoos,” Abhishek concludes.

— By Sonali Telang

Sameer Majli

The tree man

Sundays are special for Sameer Majli. When the educationist and career guidance counselor started Green Saviours 108 Sundays ago, he never imagined the bliss he would experience when little kids recognise him as the ‘Tree Man’. What better name for a person who has been engaged in creating forests in and around Belgaum in Karnataka.

With much pride in his voice, Sameer says, “Since April 10, 2016, we have planted more than 10,000 trees, 75 per cent of which have survived. We have taken the tree plantation drive to nearly 35 sites and created six mini forests. Our focus, unlike others, is on maintenance of trees; we ensure that we replant a sapling for every lost one.”

He prefers the word ‘we’ to ‘I’ because he believes it’s teamwork and it wouldn’t be fair to take the whole credit. “We are a team of 40-60 persons who engage in afforestation drives and work every Sunday without fail. There are 300 to 400 volunteers too. It’s an association devoid of designations or donations, and runs on public participation, commitment and social responsibility,” says Sameer.

The team follows an Indianised version of the Japanese Miyawaki technique of dense forest-making, where 300 trees can be planted on 10,000 sq ft of land. Each sapling is placed at a distance of eight to 18 feet from another depending on the rate of growth of the trees.

Sameer recalls, “In 2015, the rains failed and the next year, Belgaum witnessed severe drought. When scarcity hits, conservation is secondary. What came first is the thought ‘what if it doesn’t rain anymore’. Every child has learnt in school that trees bring rain; we soon put up a message on social media and a lot of people turned up.”

Since then, they have been conquering the wilderness and spreading hope. Together, Sameer and his team have built forests in industrial compounds, schools and farmlands in villages where their initiative served as a livelihood for poor farmers.

“Apart from plantation drives, we make our own saplings by harvesting the roadside ones taken out in the name of beautification. Those are transplanted to better spots and the survival rate is about 40 to 50 per cent,” he says, adding that they plant species indigenous to the Western Ghats — from local fruits like jackfruit and mango to neem, amla, tamarind, gulmohar, etc.

— By Vandana Mohadas

Shubhendu Sharma

Forest in my backyard

Shubhendu Sharma grew up in Uttarakhand, over 5,200 km away from Japan, where Akira Miyawaki lived, both unaware of each other’s existence. Shubhendu went on to become an industrial engineer at a Toyota plant where he first met the renowned botanist, naturalist and natural vegetation specialist — an encounter that changed the former’s life.

Assisting Miyawaki in cultivating a forest on the plant premises influenced Shubhendu, who developed keen interest in building green sanctuaries. After learning more about the Miyawaki methodology of forest regeneration, he replicated a model forest in the backyard of his house. He says, “That was the beginning. On 700 sq ft of land, I planted 234 trees.” Impossible it may sound, but that’s what Shubhendu and his firm Afforestt have been doing for the past seven years.

Shubhendu Sharma has created 114 jungles in 39 cities of nine countries

Shubhendu Sharma has created 114 jungles in 39 cities of nine countries

“I quit my engineering career in 2010 and launched my firm the next year in Bengaluru where we offer consultant services, contractual services, pilot projects, train people and provide manpower to build forests,” says the 29-year-old, whose first project was for a furniture manufacturer who had a policy of planting 10 trees for every tree they cut down.

The forest-making methodology, he says, is dependent on the geography of each region. Before starting work, the team takes a local flora survey to decide the potential natural vegetation and plant saplings that require minimum maintenance and very low cost. Busting the general notion, Shubhendu announces that a forest can be made in a plot as small as 200 sq metres. “While a natural forest takes 100 years to flourish, ours bring the same effect in less than a decade,” he says.

— By Vandana Mohandas

Abdul Kareem

Guardian of the wild

Dubai was called a Trucial State before it became part of the United Arab Emirates. That’s what Abdul Kareem’s passport read when he first landed there, and saw a dried up land. To plant trees they had to bring soil and water from outside. Observing it, Kareem thought of all the natural water and soil back home in Kerala. A faint dream was forming in his head — buying land and creating a kaavu (sacred grove) there. He had loved sitting at the Mannampurathu kaavu near his home at Neeleswaram, Kasargod, as a child. The dream spurred him to go to Parappa, where his wife came from, and buy five acres of land for '3,750. It was 1977. Nothing grew on that stretch of land. There was no water, no trees, no birds. Only a tiny dried up well. But today, 41 years later, Kareem is a famous man who owns 32 acres of land he has converted into a forest.

“When everyone was destroying forests, I created one,” says Abdul Kareem. In his childhood, he loved rivers and mountains and birds. Adulthood and work life had him travelling to many places, and Dubai had him yearning to go back to his old love for rivers, trees, mountains and birds. “I had a Bullet those days. I went on it to the land I bought and found there was nothing there, no trees or water. But there was a government forest 10 km away. I’d bring saplings from there. There were also adivasi families I’d help, and who’d help me with the planting. The first time there were no trees left except one — Terminalia paniculata. But that gave me inspiration. The next year we planted 200 saplings. And brought water from outside on my Bullet. Once the trees started growing, there was more water in the well. I began to learn,” recalls Kareem.

Over the years scientists from across the world came and offered tips. “When the trees started growing, I bought small pieces of land nearby. Five became 32. In ’86 I built a home there. You get the purest water here. I give it to birds, animals, people.”

He has given many interviews to international media. In one of them he said, “I will reject an offer to live in the White House or Rashtrapati Bhavan. I can’t stay away from my forest for more than two days.”

— By Cris

Jungle builders

Shyam Sundar Paliwal

Death of his baby girl prompted this villager from Piplantri to start an afforestation drive in his South Rajasthan village where everyone plants 111 trees for each newborn girl, emerging as a brand of eco feminism.

Kallen Pokkudan

The late environmental activist from Kerala is known as the protector of mangrove forests and is reported to have planted over one lakh mangrove plants all over the state.

Shyam Sundar Jyani

The sociologist from Jaipur has been planting saplings across the state for 11 years as part of what he calls the ‘familial forestry’ movement.

Rajesh Naik

He has transformed 120 acres of barren land into a lush green Oddoor farm near Mangalore by a two-acre and 50-feet deep lake there.

Radhika Anand

Aiming at planting at least 50,000 fruit trees every year since 2015, Radhika, under Mission Fal-Van, dreams of creating more green cover and oxygen for future generations and food for all.

Pamela and Anil Malhotra

Nature-loving couple Pamela and Anil Malhotra has made an over-300-acre private wildlife sanctuary SAI in Coorg which is home to animals like Bengal tiger, sambhar and Asian elephants.

M. Yoganathan

The bus conductor-turned-eco activist from Chennai has planted around one lakh tree saplings across Tamil Nadu — at least 6,000 saplings annually.

Bablu Ganguly, Mary Vattamthanam and John D'Souza

The trio has turned 32 acres of wasteland near Chennakothapalli village of Anantapur in Andhra Pradesh into a green paradise over a period of three decades.