Infusing HutK ideas in villages

At a time when ‘paid’ medical seats are casual business and doctors charge consultation fees through the roof in the name of private practice, Dr Abraham Thomas stands a class apart. An alumnus of CMC Vellore and a dentist by degree, this 42-year-old decided that sincerity was everything when he moved back to Koduru, his village in Andhra Pradesh, adopted and transformed a government school there and built a new learning centre — a space where kids — including his own — can go back to their roots, educating themselves amidst nature and traditional values. A space he calls HutK.

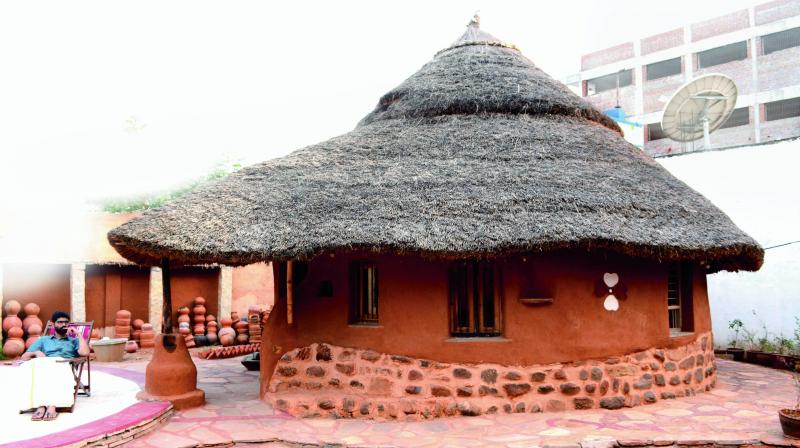

A thatched roof home in an amphitheatre, HutK is Abraham’s dream project and a tribute to his grandfather’s selfless work. “I’m a third generation doctor — my dad and my granddad before me were physicians too. I feel that there has been a quality drop in the profession and the etiquette of providing quality service has been destroyed by our policies and actions,” he says, opening up. Abraham was always socially conscious and worked with the People’s Health Movement, gaining perspective about his duties as a doctor under Dr Ravi and Dr Thelma at the Ratan Tata Institute where he did his fellowship in community health. Looking at health and education as a service to the public, and not as commercial entities, he diagnosed that his town didn’t have a public library, opportunities to learn art, an active theatre scene or a space to enhance language skills.

That was the beginning of the hut that could make a difference: HutK. “Here, we get them to unlearn first and then teach them everything from drama and elocution to singing, art, conservation, and spoken English classes to encourage creative expression,” says the doctor, who turns drama tutor, thanks to his natural flair for the subject. According to him, putting children through private schools disconnects them from the ‘ordinary.’ “You’re teaching them what’s out of their purview — even English for instance, a language that’s not their own. You’re teaching them to differentiate, and that it’s okay when it’s not,” he says. When he and his wife realised that city life wouldn’t do their kids any good, they left Bengaluru in 2008. “I decided that putting my children through a public school will give me a chance to sincerely try and change it,” says Abraham. And so he did.

He adopted the Bayana Palli MPP School in the village located about 50 kilometers from Tirupathi, eradicated the defecation problem by building up toilets — one for the boys and another for the girls, implemented solar power to save on electricity, brought in clean water supply along with gates and compound walls that a school must have, but didn’t. The school’s attendance naturally rose from 30 to 100. These successful projects only fuelled on more for Abraham, for whom renovation has now become something of a hobby.

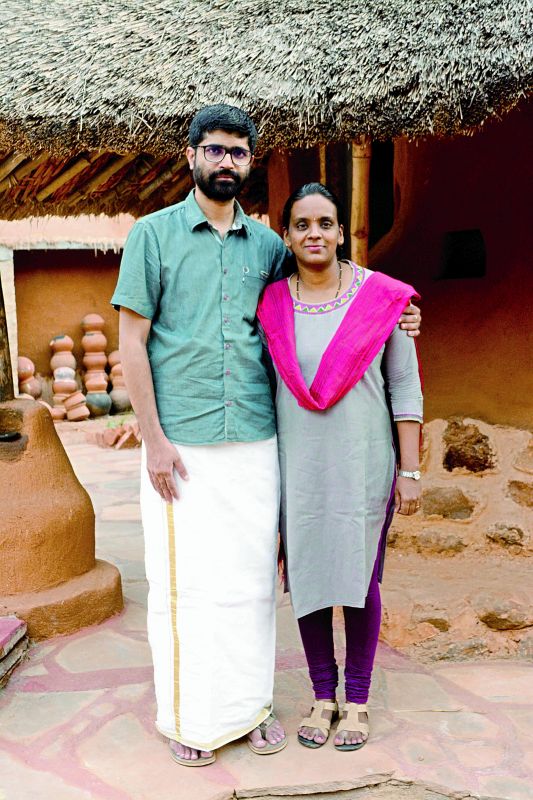

Dr Abraham Thomas and his wife Sheeba Simon.

Dr Abraham Thomas and his wife Sheeba Simon.

“I even renovated my old, ancestral home that I grew up in to keep the stories alive,” he beams, recollecting one such story: “My earliest memory is of the many rooms being stocked with everything from rice and vegetables to meat and handicrafts — things that people brought over for my grandfather because he didn’t charge them a rupee for his treatment. We didn’t have to buy a thing and these supplies lasted us all year,” he smiles. Having studied at Baldwin Boys’ High School in Bengaluru himself and understanding the importance of English in today’s globalised world, Abraham revamped the village’s first and oldest post office too, turning it into the Leela Library and Learning Centre where students can study and work on real life opportunities.

With his kids — one in Grade 4 and the other in Grade 6 moving to the Government High School established in 1952, he now wants to lend his magic to it too. “It’s on a 14-acre land and in tatters. I want to get an architect, dream, draw and re-draw to make it better,” he says, his vision including laboratories with microscopes and a field where Kabaddi competitions can be held again. All of this, he says, wouldn’t have been possible without the unconditional support of his family. His wife Sheeba Simon whom he talks adoringly about, is a lawyer and worked at the Bishop Cotton Women’s Christian Law College before her move to Koduru.

“She even did a diploma in English teaching from the Regional Institute of English in Bengaluru so she could teach the village kids here,” says Abraham. His brother Samuel Thomas, an environmentalist with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and his sister-in-law Anamika, a gifted Paubha artist also pitch in at the school. “We have a talented in-house staff!” he quips. While he strives to give a face lift to his village, he admits that he’s not a super hero. “I can do this for people around me. But if communities adopt their schools and be involved in the education of their children, imagine the huge implications for rural education and significant financial implications for rural households...” he says, his eyes firmly set on the future, his next project, already on his mind.