Relics on print

But o, photography! as no art is,/Faithful and disappointing! The British poet Philip Larkin wrote those “lines” on “yielding to a young lady’s photograph album”, ruminating on the vain attempt at restoring the past for the future.

But to commemorate their 10th anniversary, Tasveer, a pan-India gallery headquartered in Bengaluru, is showcasing 19th century vintage photographs of India by colonial photographers Samuel Bourne, Charles Shepherd and their Bourne & Shepherd studio, that would make viewers imagine India of the past — India at the break of dawn of ‘dreaming big’. The photographs mostly consist of architectural views, landscapes and portraits of their patrons and clients.

Varanasi (formerly Benares), Vishnu temples on the Ganges.

Varanasi (formerly Benares), Vishnu temples on the Ganges.

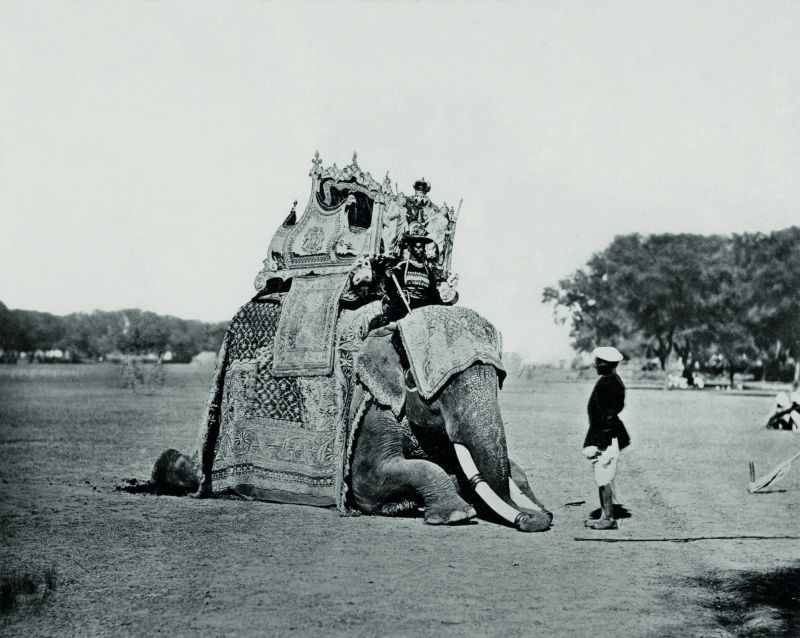

Delhi, His Eminence, The Viceroy’s Elephant, Delhi Durbar.

Delhi, His Eminence, The Viceroy’s Elephant, Delhi Durbar.

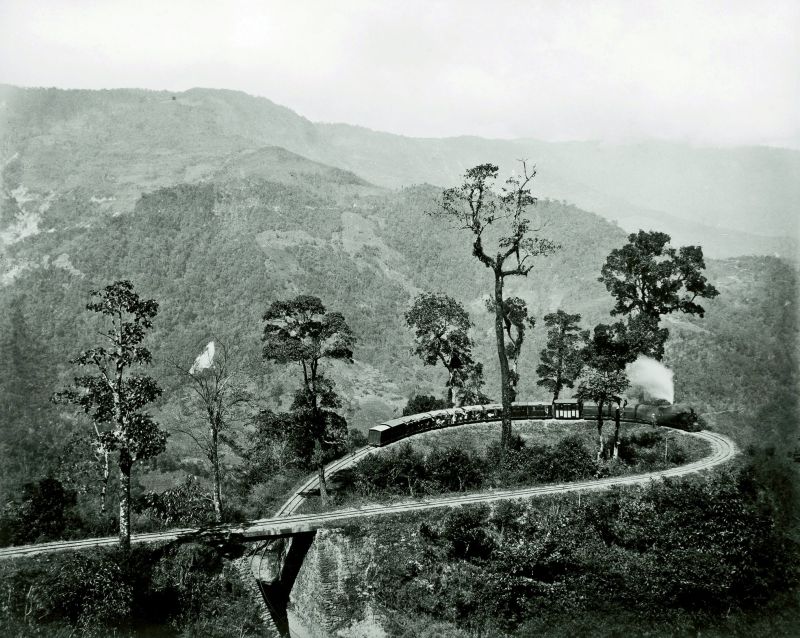

Darjeeling, the loop on the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway image courtesy: MAP/Tasveer.

Darjeeling, the loop on the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway image courtesy: MAP/Tasveer.

In a foreword to the ongoing exhibition, Shilpa Vijayakrishnan writes, “One of the most famous of the early European commercial photographers-cum-adventurers, and the most prolific photographer of the picturesque, Samuel Bourne arrived in India in 1863. A former clerk in a Nottingham bank, Bourne abandoned his position in favour of a photographic career in India that seemed to combine beautiful landscapes with an expanding commercial potential. Undertaking several expeditions in the seven years he spent here, including some extremely perilous journeys, Bourne photographed the expanse of Imperial India: from the Himalayas down to Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka). Particularly influential over the visual regime of nineteenth century, especially translating as tourist souvenirs and postcards, his photographs produced a visual culture that packaged and represented a specific idea of India.”

Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), Old Court House Street, 1867.

Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), Old Court House Street, 1867.

Delhi, The Great Arch and the Iron Pillar at the Qutub Minar.

Delhi, The Great Arch and the Iron Pillar at the Qutub Minar.

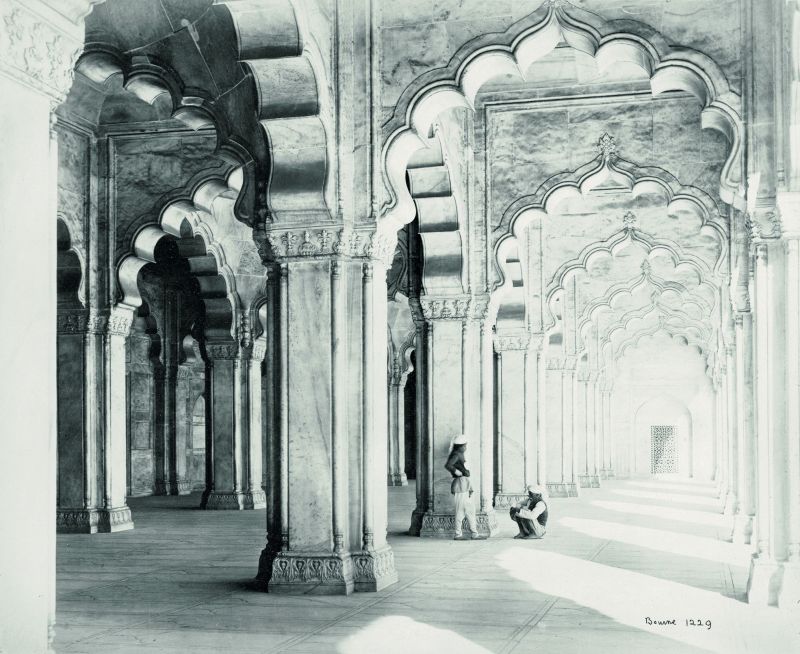

Agra, the interiors of the Moti Masjid.

Agra, the interiors of the Moti Masjid.

With William Howard, he established the photographic studio Howard & Bourne in 1863. Later they expanded to include Charles Shepherd. In 1866, the Bourne & Shepherd establishment set up a branch in Calcutta, which shut shop in 2016.

Hugh Ashley Rayner in his essay on the life and photographic work of Samuel Bourne notes, “Even though he produced one of the finest bodies of photographic work in the history of photography in India, his name is still largely unknown, both in India and in the rest of the world, except amongst a very small number of collectors and students of photographic history.”