Monumental legacy

Noted architectural historian, Giles Tillotson’s book on the country’s capital, provides a fascinating account of its architectural heritage.

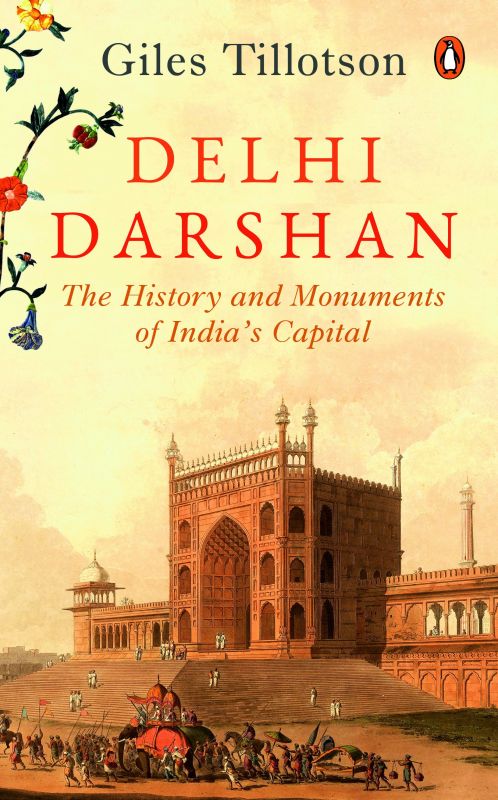

Delhi has had a long-standing association with India’s epic past. Local legends pin the fabled capital of Indraprastha from the Mahabharata to an area near Purana Qila. “Modern excavations have indeed revealed very early pottery remains, confirming that identification for those who are willing to believe in it,” writes architectural historian Giles Tillotson in his book Delhi Darshan: The History and Monuments of India’s Capital. While multiple authors have explored the various facets of city, Tillotson perseveres to unravel the story behind the birth of Delhi and the forgotten history of its historical monuments, besides suggesting routes to trace the bygone era minutely.

Delhi Darshan: The History and Monuments of India’s Capital by Giles Tillotson penguin books Pp. 183, Rs 499.

Delhi Darshan: The History and Monuments of India’s Capital by Giles Tillotson penguin books Pp. 183, Rs 499.

The book completes his trilogy of the Golden Triangle of India. In 2006, the author came up with Jaipur Nama, which chronicled the architectural history of the pink city and followed it up with Taj Mahal in 2008. The book takes us through Delhi’s origin when seven cites— all Islamic citadels— came together. “I have known Delhi for 40 years, and have visited most of the monuments, many times. I have been researching the history of Delhi throughout my career. All this experience goes into the book,” shares Tillotson who reveals how the city may have got his name. “Its origin and meaning are forgotten. Some historians interpret it to mean ‘threshold’, marking it as the point of entry into India for conquerors from the other side of the Hindu Kush. A rival claim associates it with an earlier and more local hero, Raja Dhilu. Each theory has its confident adherents but neither of them persuades everyone,” he writes.

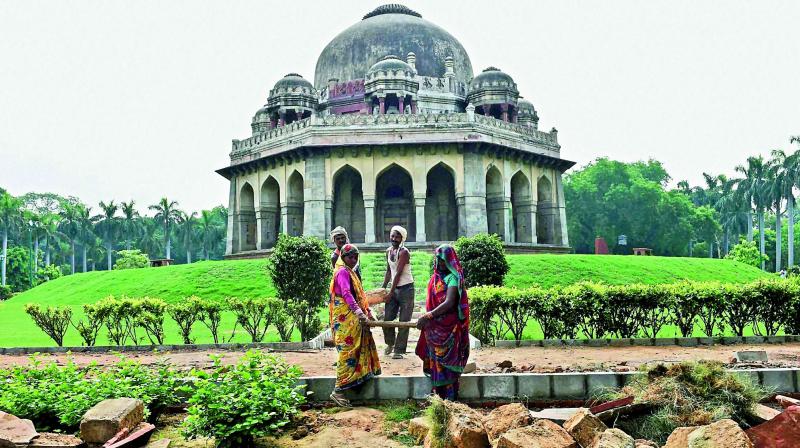

From Rajputs to Mughal emperors to finally the British Raj, Delhi or Dilli, over centuries, has been the centre of power for various clans. It was through these various reigns in the city — Sayyids, Afghans, Turkic and British — that Delhi got its character and features from the legacy left by each ruling kingdom. For instance, Humayun’s tomb is not only the burial place of one of the early Mughal emperors, it is also the place where his last ruling descendant, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was arrested, at the bloody denouement of the 1857 uprisings. Another example is that of Lodhi Garden that must have been garden even during the rule of Lodhis in the 15th century. “But all trace of it vanished long ago, and by the nineteenth century it was the site of a village called Khairpur. In 1936, the poor villagers were evicted and the whole area was landscaped in English picturesque mode to create a London-style urban park, named Lady Willingdon Park. Her name survives, carved in a stone gateway on the northern side. But on

ly there. In the 1960s, Jawaharlal Nehru commissioned the architect Joseph Allen Stein to adjust the landscaping. The pond was added and the gardens were renamed after the Lodis, the original proprietors,” he mentions.

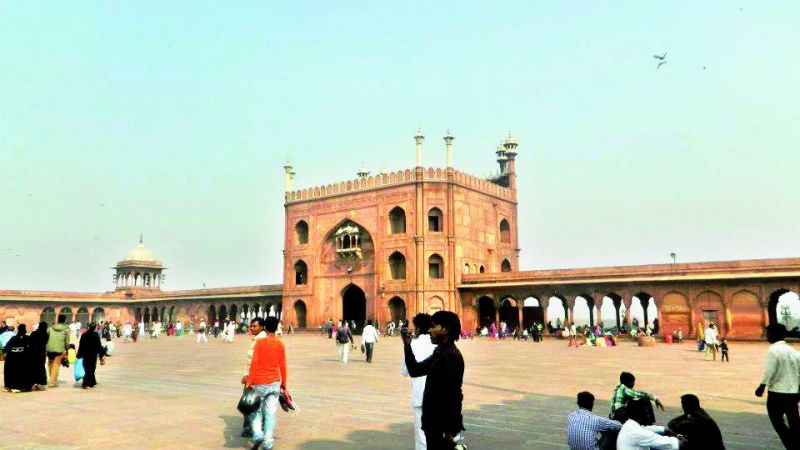

The author also chronicles how early Sultans destroyed temples to construct mosques. A glimpse of their act can still be seen at Quwwatu’I-Islam mosque—first of the seven cities — that holds the inscription at the eastern entrance, recording that no less than 27 Hindu and Jain temples were demolished for its construction. “The colonnade that encloses the mosque’s earliest and inner courtyard is entirely composed of temple columns. Though here redeployed in the service of a different religion, they still bear the carvings that relate to their former use: depictions of hanging bells, overflowing pots, the mask-like kirtimukha or ‘face of fortune’, abundant foliage and even, in a few cases, figures of human form.”

However, for Tillotson, this appropriation of ancient sacred sites by new powers is not unique to India and finds this practice common across religions. As the following chapters then bring to fore the religious clashes between dynasties, the author believes it was important to tell the story of Hindu-Muslim relations in a nuanced way. “By avoiding the polarisation of politicians or the bland denial of some academics. It is clear to me that the early Sultans identified themselves, as—among other things—Muslims establishing power on the periphery of what they thought was the civilized world. In this sense, they viewed South Asia in the same way as a 1st-century Roman would have viewed Britain,” says Tillotson. At the same time, he maintains that the book was written to discuss the history, architecture and shouldn’t be looked at with communal perspective. “I have not presented a modern political history of the city as this is not my area of expertise,” he adds.

To break the monotony of the historical data, author’s narration of facts by world traveller Ibn Battuta lightens up the mood. “He is an interesting and evocative source. But it is hard to know how dependable he is. For example, he says that the Quwwatul Islam mosque is ‘white’. Is this idealization? Or was it plastered? We don’t know,” he laughs.

But Tillotson’s favourite ‘lost’ monument is the swimming pool of Jaipur House that was destroyed in the 1990s to make space for the fine new extension. Of the seven cities, Shahjahanabad makes to the author’s list for it still continues to be a living city. “What I really appreciate most is not the particularities of this or that era, but the manner in which they interact,” he muses.