Running towards disaster

While the subject may be serious, the author weaves a vivid story that is endearing, humorous, romantic and heartbreaking in parts.

Anita Rose, the daughter of a poor Christian masseuse living in Karachi; Monty, a rich kid in the same city and Sunny, the son of an Indian immigrant living in Portsmouth belong to different worlds but their vulnerability, lack of a proper emotional support structure and the need to belong takes them on a journey to a jihadi camp in Syria and finally, towards Islamic extremism.

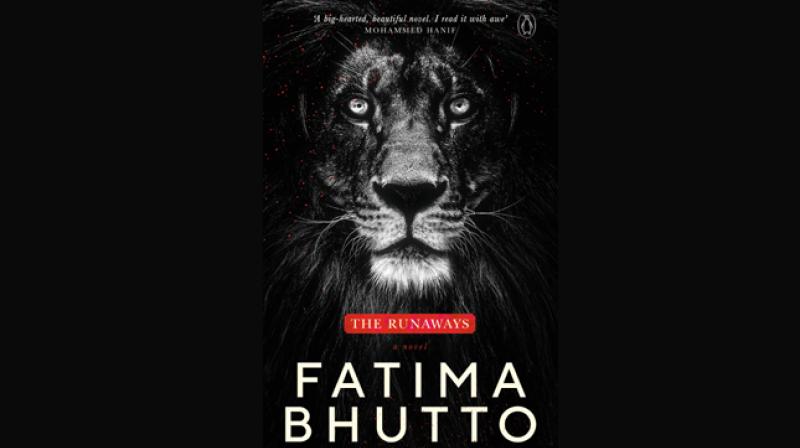

The Runaways by Fatima Bhutto is a fantastic read which makes the reader understand why so many youngsters from Britain, Australia and other parts of the West have been fleeing the security of their everyday lives and becoming Jihadi brides or ISIS fighters. Through the lives of the main characters, Bhutto reveals how dissatisfaction and alienation can lead youngsters to do unimaginable things like becoming radicalised.

While the subject may be serious, the author weaves a vivid story that is endearing, humorous, romantic and heartbreaking in parts. You really feel for the characters and want to reach out to them and say, “No! Don’t go there!”

The irony of Anita Rose’s life is that the one constant figure of genuine friendship and kindness actually sets her on a path to terrorism.

Osama, her elderly neighbour and only friend who for years is the family’s go-to man for free groceries and other necessities, introduces her to literature that celebrates fighters and genuine heroes — “Men he had known who believed in something great, of writers who opposed oppression and injustice.”

This sadly triggers her anger towards society and classmates who make it known to her that she doesn’t belong with them.

For a girl who wants nothing more than to hang out with and live the life of all the rich kids with their beautiful homes in Karachi’s upmarket Clifton, Syria becomes her destination instead. Monty, on the other hand, has everything going for him as the only child of one of Karachi’s richest businessmen. But his neurotic mother and emotionally absent father, who believes Monty needs to man up, do not give him the security that he craves.

The Ahmeds do however, provide some humorous moments. Monty’s dad’s annoyance over talkative cabbies who just won’t shut up when they fetch you from Heathrow in London is so relatable. When the Uber driver asks Monty’s dad if he needs anything, all he says is, “Silence!” His disdain towards a maulvi that his wife suddenly starts to follow is also very funny.

Sunny, the book’s other main character, is the best sketched out figure. His father, an Indian immigrant who comes to England dreaming of going to Ascot, becoming English and turning into a huge success story is as comical as it’s tragic. Trapped in an unhappy marriage, he tries to make a life for his family in Portsmouth but simply tries too hard.

Stuck with a slightly cuckoo father, who also makes for an excellent nag, Sunny is confused about his sexuality and really doesn’t know who or what can make life happy. All those desi girls in hijab who are wild in bed or the white girls who find Sunny super hot also don’t do it for him anymore. He turns towards religion in the hope of finding salvation but it’s his attraction towards his cousin Oz that finally pushes him towards Syria.

Fatima Bhutto

Fatima Bhutto

Author Fatima Bhutto, a Pakistani born in Afghanistan, has lived in Syria and experienced the tragedy that comes with being born into one of the world’s most powerful political dynasties. No wonder then that she is best suited to tell the tale of youngsters growing up in a painful world, making The Runaways such a relatable and relevant read.

‘I believe in redemption as a principle’

Q The Runaways is such a great work. How long did it take you to put it together? How did you go about your research?

I spent about four years writing the novel and rewriting it several times. It began as a much shorter book and more driven by the news and current events but with every draft, I moved away from the news and more into the inner life, the troubles and the hopes of the characters. While the first half of the book is completely focused on who Sunny, Monty, Anita Rose and Layla are, the second half places them in conflict with the wider world. Part of the book was based on things I’ve observed over the years — the loneliness, confusion and isolation of not belonging — and then another part, particularly to do with the day-to-day life of someone fighting in Iraq, came out of reading and watching a lot of accounts of young people who had left their homes and families to join extremist movements.

Q Your book finally makes one understand why so many British teenagers have been running away to Syria to join ISIS. How do you think they can be prevented from making this mistake?

Compassion. If those teenagers — not just in Britain but anywhere in the world — had felt their society valued and respected them and that they had a role to play in the future of their country or community, then I doubt they would have left their homes to take up arms against the world. The compassion towards and inclusion of people who feel relegated to the periphery has to be there before they make these devastating choices.

Q One can’t help but feel sorry for them, do you think that at least a few deserve a second chance or they just have to deal with the consequences?

I believe in redemption as a principle. One must always have space for empathy and redemption but I also recognise that people have to be held responsible for their actions — especially when they are motivated by anger and violence. But that is the beautiful thing about novels, they demand empathy of you before anything else. And that’s a good guide for life in general.

Q For someone who was born in Afghanistan, lived in Syria and born into a famous politics dynasty in Pakistan, how much did your heritage help you own this novel?

I come from so many places and feel an affinity with the countries you mentioned — from Afghanistan to Syria — and that, I suppose, makes me open towards places that most people are unsure about because they have only heard of them from a distance. I’ve always been interested in people on the fringe and those who would otherwise be cast in the darkness, but this novel was not so much influenced by my past as by the present and what I felt when I looked at the world around me right now.

Q You have been through so much tragedy in your life but still believe in the importance of peace and have not let your life only be coloured by tragic events. What gives you that strength which the characters in this book lack? How did you deal with the hardships?

I was deeply loved. I was raised by a father who gave me his time, his love and his attention - that's what saved me and continues to save me today. Even 23 years after my father, Murtaza, was assassinated, it is his love that nurtures and protects me. In this, I know I am incredibly fortunate and I thank God every day for giving me the gift of my father, even though I only had him for a very short time.

Q Poverty, the desperate need to fit in, loneliness and wrong company are what prove to be the characters’ undoing.... in Sunny and Monty’s case their parents can be blamed to a certain extent, but what about Anita Rose’s mum? Do people like that have any chance?

Anita Rose’s story is set against the backdrop of burning inequality. The depravations she endures are more painful, more haunting and unremitting. None of the characters are motivated by religion, which alone is not the cause of radicalism in the world today. But how do we judge a girl who has to fight for the most basic rights? Who will have nothing — no chance at life, who is rendered powerless and invisible by the poverty of her birth — unless she battles for it? How do we condemn her for wanting a different life?

Q What do you have to say about a character like Ozair? Should we applaud him for turning his life around in time or despise him for destroying another life?

Without giving away too many spoilers, I think Ozair is not what he seems. Rather, he’s never what he seems and I’m not sure I can applaud a character so easily flexible with his ethics and morals. He’s not someone I trust either...

Q When you look at Syria today how do you feel? Can it ever become the Syria you lived in?

It’s heartbreaking to see what Syria and the Syrian people have been through and I could have never imagined such a scale of horror taking over a country that I love, but I have faith that Syria will recover.

It will certainly take time, but I have hope. Syria is a country that has survived through millennia with its heart and soul intact.

Q What next? How are you unwinding now?

Right now, I’m on the next leg of the book tour, I just finished the UK part of the tour and am preparing to head to Australia where I'll be speaking at the Sydney Writer’s Festival. There’s not a huge amount of unwinding yet but I’m enjoying going back to books and reading for pleasure rather than for research! I just read an utterly gripping non-fiction book called Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe (it’s about the troubles in Ireland, so I wouldn’t call it ‘unwinding’ material but fascinating nonetheless!)

Q When can we expect your next novel?

My next book is going to be non-fiction, it’s a narrative reportage on the end of the American century of soft power and the new centres of global pop culture rising up in India, Turkey and Korea.