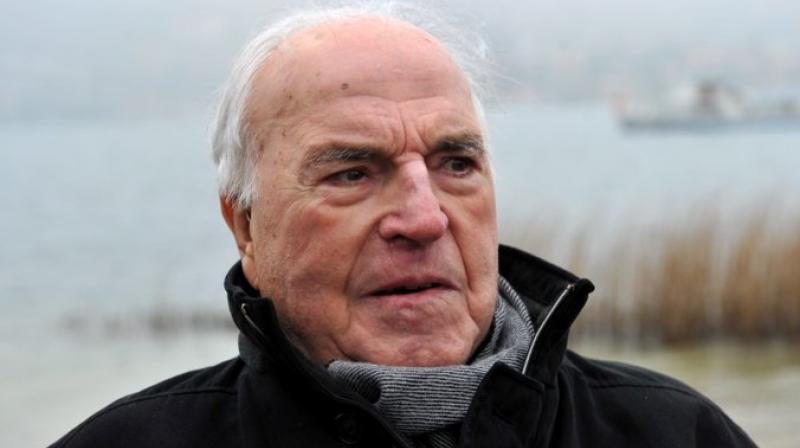

Helmut Kohl, chancellor who reunited Germany, dies at 87

Berlin: Helmut Kohl, the physically imposing German chancellor whose reunification of a nation divided by the Cold War put Germany at the heart of a united Europe, has died at 87.

Kohl’s Christian Democratic Union party posted on Twitter: “We are in sorrow. #RIP #HelmutKohl.” The daily newspaper Bild reported that Kohl died Friday at his home in Ludwigshafen.

Over his 16 years at the country’s helm from 1982 to 1998 first for West Germany and then for all of a united Germany Kohl combined a dogged pursuit of European unity with a keen instinct for history.

Less than a year after the November 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, he spearheaded the end of Germany’s decades-long division into East and West, ushering in a new era in European politics.

It was the close friendships that Kohl built up with other world leaders that helped him persuade both anti-communist Western allies and the leaders of the collapsing Soviet Union that a strong, united Germany could finally live at peace with its neighbors.

“Helmut Kohl was the most important European statesman since World War II,” Bill Clinton, the former US president, said in 2011, adding that Kohl answered the big questions of his time “correctly for Germany, correctly for Europe, correctly for the United States, correctly for the future of the world.”

“The 21st century in Europe really began on his watch,” Clinton said, describing Kohl as “a man who was big in more than physical stature.”

Famed for a massive girth on his 6-foot-4 (1.93-meter) frame, Kohl still moved nimbly in domestic politics and among rivals in his conservative Christian Democratic Union, holding power for 16 years until his defeat by center-left rival Gerhard Schroeder in 1998.

That was followed by the eruption of a party financing scandal which threatened to tarnish his legacy and for a time plunged the CDU into crisis. For foreigners, the bulky conservative with a fondness for heavy local food and white wine came to symbolize a benign, steady even dull Germany.

Kohl’s legacy includes the common euro currency that bound Europe more closely together than ever before. Kohl lobbied heavily for the euro, introduced in 1999, as a pillar of peace and when it hit trouble more than a decade later, he insisted there was no alternative to Germany helping out debt-strapped countries like Greece.

Once viewed as a provincial bumbler, Kohl combined an understanding of the worries of ordinary Germans with a hunger for power, getting elected four times.

Kohl served longer than Konrad Adenauer, West Germany’s first post-World War II chancellor and his political idol. Only Otto von Bismarck, who first unified Germany in the 1870s, was chancellor longer, for 19 years.

“Voters do not like Kohl, but they trust him,” Rita Suessmuth, a former speaker of parliament, once said.

Often harsh and thin-skinned, Kohl also could display a quick wit and jovial earthiness that served him well in building up German clout. He ate pasta with Clinton and took saunas with Russia’s Boris Yeltsin.

Kohl linked his dedication to a united Europe to his roots in a part of Germany close to France and his memories of a wartime boyhood. He celebrated the European Union’s eastward expansion in 2004 with a speech declaring that “the most important rule of the new Europe is: There must never again be violence in Europe.”

Still, the “blooming landscapes” that Kohl promised East German voters during reunification were slow to come after the collapse of its communist economy, and massive aid to the east pushed up German government debt. He also drew criticism for failing to embark on economic reforms.

Born on April 3, 1930, in Ludwigshafen, a western industrial city on the Rhine, Kohl joined the Hitler Youth but missed service in the Nazi army. As a 15-year-old, he was about to be pressed into service in a German anti-aircraft gun unit when World War II ended. His oldest brother, Walter, was killed in action a few months earlier.

A Roman Catholic, Kohl joined the CDU in his teens shortly after its postwar founding. He earned his doctorate in 1958 at the University of Heidelberg with a dissertation on the politics of Rhineland-Palatinate and became governor of that western state in 1969.

His first attempt to unseat Social Democratic Chancellor Helmut Schmidt failed in 1976, but Kohl seized his chance six years later, taking power on Oct. 1, 1982 when a junior coalition party switched sides.

He won elections in 1983 and 1987, then rode to an election triumph in 1990 on a wave of post-unity euphoria.

Kohl was reluctant to view united Germany as a major power because of the Nazi past. Still, he slowly edged his country toward greater responsibilities in the 1990s, as Germany sent troops for UN humanitarian missions in Cambodia, Somalia and elsewhere, and deployed peacekeepers to Bosnia.

He pursued reconciliation with Germany’s eastern neighbors, though some critics said he moved too slowly after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Kohl was helped in securing German unity by his friendships with French President Francois Mitterrand and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who approved NATO membership for a united Germany and agreed to pull Soviet troops out of East Germany.

Kohl’s earlier bridge-building with the US also paid off. The stationing of US Pershing II missiles starting in 1983, despite huge domestic protests, had established trust in Washington that was crucial to creating a single German state.

“It was a stroke of luck that there were about four to six leaders in power in the mid-80s who really trusted one another and could really make things happen,” Kohl later recalled. In his memoirs, he described former US President George H.W. Bush as “the most important ally on the road to German unity.”

He praised former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher for her honesty, even as he recalled a confrontation with her just a few days after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

“I cited a 1970s-era NATO statement and said that NATO supported reunification. Thatcher stamped her feet in anger and screamed at me, ‘That’s how you see it! That’s how you see it!’” he wrote.

In a poignant gesture of reconciliation in 1984, Kohl held hands with Mitterrand during a ceremony at a World War I cemetery in Verdun, France.

Another gesture of friendship and reconciliation the following year turned into a public relations fiasco. Kohl’s trip with then-US President Ronald Reagan to a war cemetery in Bitburg where SS troops were buried alongside ordinary German soldiers generated international indignation.

Kohl’s relationship with Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, also had to overcome early turbulence. In a 1986 interview, Kohl was quoted as comparing Gorbachev’s public relations skills with those of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. The Soviet Union protested.

Elation over German reunification ebbed amid the harsh realities of its cost and the difficulties of integrating east and west, but Kohl’s coalition squeaked by again in 1994. Yet high unemployment and Germans’ yearning for change gradually sapped his authority, provoking a humiliating loss to the younger Schroeder’s center-left Social Democrats in 1998.

The following year, Kohl plunged his party into crisis when he admitted accepting undeclared and therefore illegal donations during his time as chancellor. Kohl refused to identify the donors, to whom he said he had given his word.

His silence helped trigger a parliamentary inquiry and was condemned by many, both inside and outside his party, but Kohl vehemently denied that any decisions by his government were bought.

When Bonn prosecutors launched an investigation into possible breach-of-trust charges in January 2000, Kohl was pressured to give up his party’s symbolic honorary chairmanship notably by Angela Merkel, a longtime Kohl protegee who served for seven years in his Cabinet and followed him into the chancellery in 2005.

In a 2001 deal with Bonn prosecutors, the probe was dropped in exchange for a 300,000-mark fine (about $140,000 at the time) giving Kohl the legal stamp of innocence. That was a common German practice, not considered special treatment, but judicial investigations into other figures in the murky financing scandal continued.

In another battle after his departure from power, Kohl fought and won a lengthy legal fight to prevent the release of most of the files held on him by East Germany’s secret police. Journalists and historians had asked to see the material, prompting speculation it could shed light on the financing scandal. Kohl, however, argued successfully that the wiretaps used by the Stasi to spy on him were illegal and that he deserved protection from damage to his “human dignity.”

Kohl’s estrangement from his party lasted until 2002, when its new leaders invited him to speak at a convention as they sought to regain power.

The former chancellor was married for 41 years to Hannelore Renner, an interpreter of English and French who stood firmly but discreetly by his side throughout his political life. They had two sons, Peter and Walter.

In July 2001, Hannelore killed herself at age 68 in despair over an incurable allergy to light. In 2005, Kohl introduced his new partner Maike Richter, an economist some 35 years his junior. The couple married in May 2008.

Though slowed by illness in his later years, Kohl still made occasional eye-catching interventions on the political stage. As Merkel struggled to convince center-right lawmakers in 2011 of the wisdom of having Germany finance further bailouts of other eurozone nations, Kohl weighed in firmly. “There must be no question for us that we in the European Union and the eurozone stand by Greece in solidarity,” he declared.

He also appeared to question Merkel’s approach at a time when conservatives were unsettled by her decision to speed up Germany’s exit from nuclear energy and by Germany’s abstention in a U.N. vote on a no-fly zone over Libya. “I ask myself where Germany stands today and where it wants to go,” he said.

In April 2016, Kohl welcomed Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban who had clashed with Merkel over Europe’s approach to a large influx of refugees to his home. That coincided with the publication of a new foreword to a Kohl essay in which the ex-chancellor stated that “Europe cannot become the new home for millions of people in need worldwide.”

Kohl and Orban said, however, that they saw no conflict with Merkel’s efforts to solve Europe’s migrant crisis.